Made by Monks

Christian monastic life began with St. Anthony, in lower Egypt, in 271 ACE. Anthony and the monks who followed him were solo monks, hermits, going by themselves into the desert. By next century, groups of monks were gathering together in communities. The first monk to apply organization to large communities of monks was Saint Pachomius (286-346). His organizational reforms led to monasteries spreading out of Egypt into Palestine and Syria. Two centuries later, Saint Benedict introduced new reforms in monastic life. Afterwards, Benedictine monasteries spread throughout Europe.

Now, the thing with European monasteries in the Middle Ages is that they were often comparative economic powerhouses next to their parishioners. Considering that a guiding goal of monastic life since Anthony had been simplicity and low material wealth, such abundance was a problem. Thus, in 1098, a group of Benedictine monks, complaining that large monasteries had lost their way, broke off and formed their own monastic order in Citeaux, in east central France.

These monks became the first Cistercian order. Whereas all the traditional Benedictine monasteries were under the authority of their European source, the Great Abby of Cluny, Cistercian monasteries were related and complimentary, but independent, cells. However, over the centuries, even the Cistercians became established and prosperous. Thus, in 1637, when a French noble renounced his wealth and became a monk, he inspired a whole new “back to basics” reform movement among the Cistercians. Playing off of a childhood nickname, “the Abbott of La Trappe,” the new orders grew to be called Trappists.

One of Benedict’s core monastic tenets is "ora et labora” (“prayer and work”). Monks and nuns are meant to pray and occupy themselves with manual labor. Another tenet is the dedication to good works. Thus monasteries grew to make goods that were beneficial to their surrounding communities — clothes, bread, cheese, etc. The monks sold these goods to cover the monastery’s expenses and were supposed to invest any profit back into the community. Since monasteries were already making beer for their own use — as it was a staple of household diets — it didn’t take much for Trappist monasteries to develop a tradition of commercial brewing. Today, there are only thirteen Trappist breweries in the world, and the Trappist beers from Belgium, in particular, are some of the finest beers in the world.

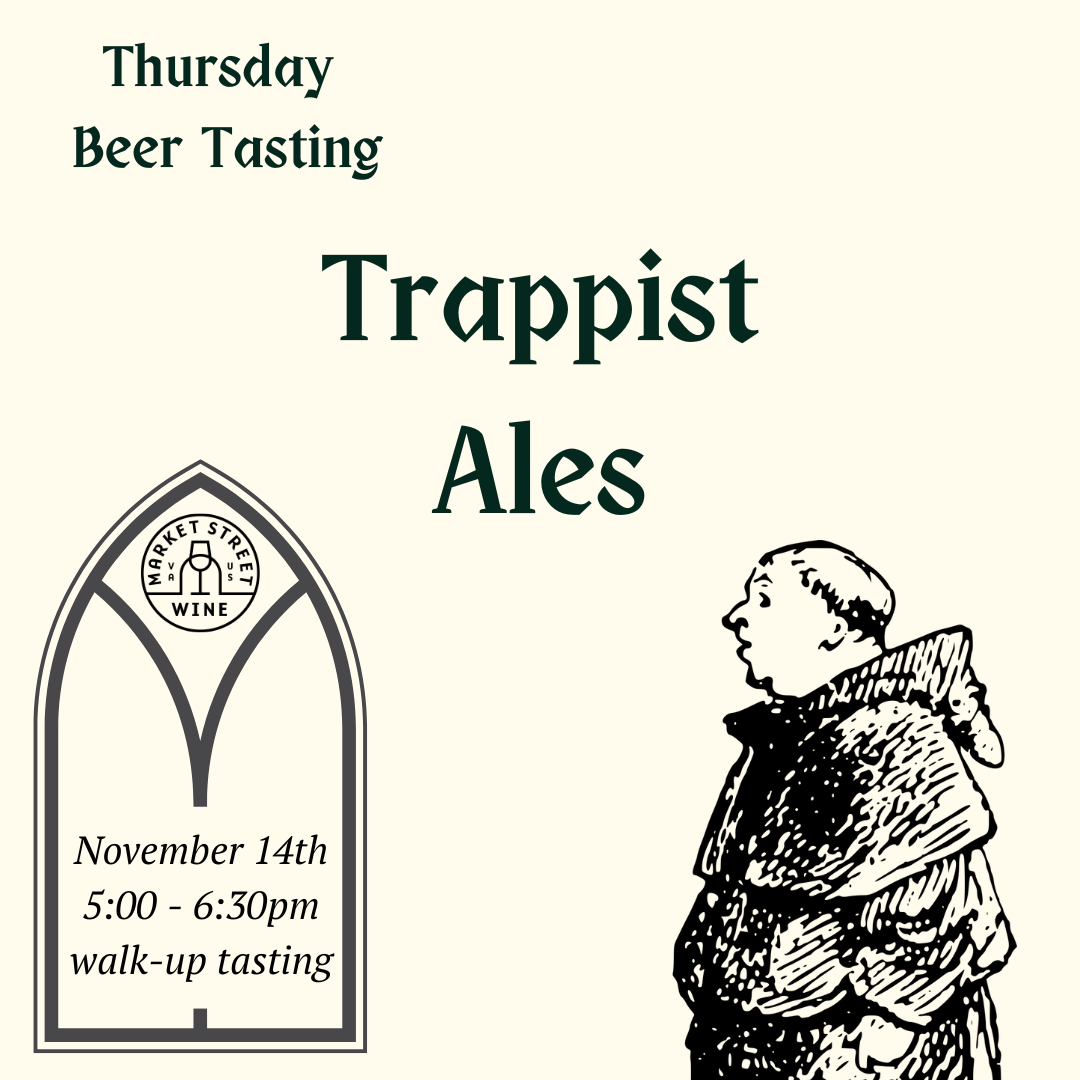

Please join us this Thursday for a tasting of Trappist beers. This is a free, walk-up tasting. Feel free to come by any time in the hour and a half.